Over the last decade, India has witnessed a profound transformation in the relationship between citizenship, identity, and the state. While legally all citizens are equal under India’s constitution, the emergence of Hindutva as a dominant ideological framework has created a parallel system of belonging one defined not by law but by religion, culture, and allegiance. The result is a nation where millions are citizens on paper but are increasingly treated as outsiders in their own country.

The roots of this crisis lie in the political codification of Hindutva, an ideology that equates nationhood with a singular religious and cultural identity. While Hinduism has historically been pluralistic, encompassing diverse sects, castes, and regional practices, the Hindutva framework seeks to consolidate these differences into a monolithic narrative. Under this lens, loyalty to India is closely tied to adherence to this singular vision of culture and religion. Those who fall outside it particularly Muslims, Christians, and Sikhs are viewed as perpetual outsiders, regardless of their legal status or generational ties to the country.

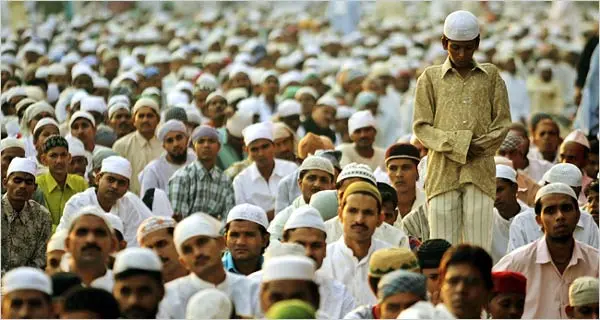

This ideological framing has been reinforced through legislation. The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) of 2019, for instance, introduced a religious dimension to the concept of belonging, providing a fast-track path to citizenship for non-Muslim refugees from neighboring countries. When paired with the proposed National Register of Citizens (NRC), it has created a scenario where millions of Indian Muslims could face intense scrutiny, effectively turning a constitutional guarantee into a conditional privilege. Estimates suggest that India’s minority population—over 28 crore people, or roughly 19.3% of the total population now lives under the shadow of potential exclusion.

The crisis extends beyond Muslims. Sikhs and Christians have faced systemic marginalization and cultural erasure. Sikh identity is often denied or subsumed under Hindu narratives, while Christians have seen a staggering rise in attacks on their communities, with incidents increasing from 127 in 2014 to 834 in 2024, according to the India Hate Lab Report. Legislative efforts such as the 2024 Waqf Amendment Bill have further intensified the sense of alienation by granting the state authority to interfere in the administration of Muslim religious properties.

The consequences of this ideological shift are both social and generational. Social polarization has deepened, fostering mistrust between communities and encouraging the ghettoization of those who no longer feel safe in mixed neighborhoods. Hate rhetoric has become normalized, and institutions from police to judiciary are increasingly seen as partisan actors in identity politics. Meanwhile, a significant brain drain is underway, as skilled professionals and young talent seek opportunities in countries where pluralism and rule of law are more secure.

Electorally, this strategy has proven effective. The ruling party has consolidated a broad Hindu vote bank by portraying minorities as a civilizational threat. But politically efficient strategies come with a steep social cost. Alienating nearly a fifth of the population undermines the foundations of democracy, erodes social cohesion, and weakens the country’s capacity for governance. The legal identity of citizens may remain intact, but ideological alienation has created a parallel hierarchy of belonging, one where constitutional guarantees are subordinate to religiously defined loyalty.

India’s identity crisis is thus not temporary or incidental it is structural. The challenge facing the country is how to reconcile its legal commitments with the pressures of a dominant ideological narrative that treats large portions of its population as outsiders. Without addressing this divide, India risks entrenching social fragmentation, weakening institutions, and eroding the pluralistic character that once defined it on the global stage.